MINUSMA – Actors of Conflict in Mali

Jihadists

JNIM

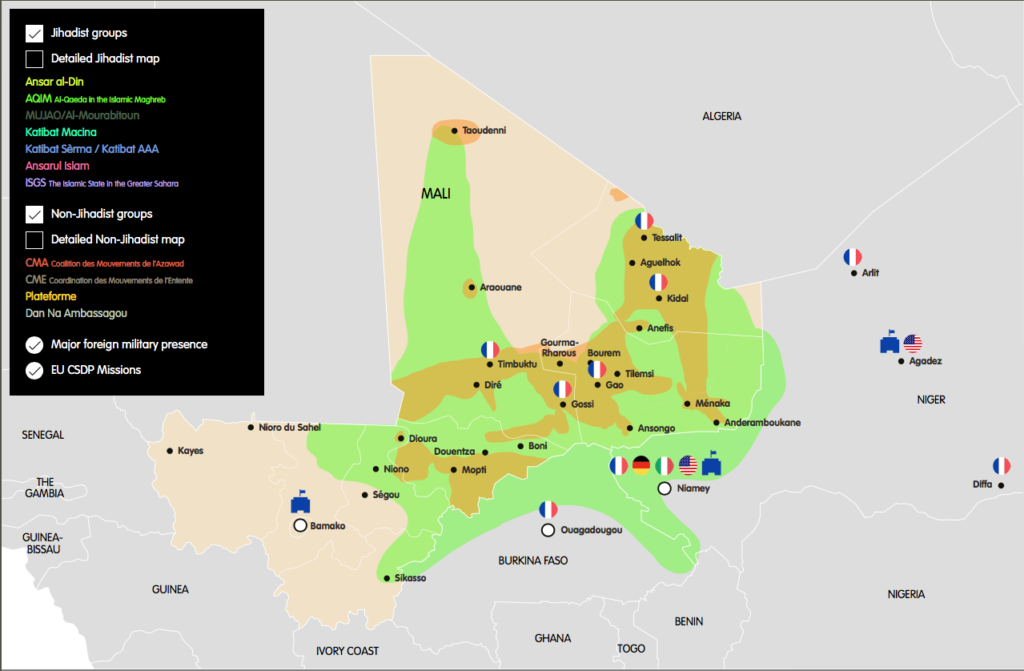

JNIM, an umbrella coalition of al-Qaeda-aligned groups, announced its existence in March 2017 in a video release featuring the leaders of its component parts – Ansar al-Din, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), al-Mourabitoun, and Katibat Macina. Headed by Tuareg militant leader Iyad Ag Ghali, JNIM has since established an independent media arm and regularly claims responsibility for attacks throughout Mali. It took credit for the January 2019 attack that killed ten UN peacekeepers in Aguelhoc, recent devastating attacks on Malian army bases in Dioura and Guiré, and several attacks against security forces as well as other armed groups in Niger and Burkina Faso.

Broadly speaking, JNIM’s aim is to drive foreign (especially French and UN) forces out of Mali, and to impose its version of Islamic law. It maintains its allegiance to al-Qaeda and seeks to spread the reach of jihadist groups in the region. Although the components within JNIM act relatively autonomously, they have still consistently reaffirmed their membership in the umbrella group. Katibat Macina leader Amadou Kouffa in particular has consistently confirmed the centrality of Iyad Ag Ghali to the movement and to any potential negotiations with them. Despite heavy losses at the hands of French forces, JNIM continues to operate throughout Mali and into Burkina Faso and Niger, conducting complex attacks, assassinations, and improvised explosive device (IED) attacks on UN, Malian, and French forces.

“KATIBAT SÈRMA” AND KATIBAT AAA

According to local sources as well as international security observers, these groups are largely autonomous collections of fighters associated with JNIM. One was formerly headed by a Malian National Guard member and Imghad Tuareg Almansour Ag Alkassoum (whose initials constitute the “AAA”), and the group has continued to operate extensively between the Malian towns of Douentza, Boni, and Hombori. It is also believed to have conducted some operations in Burkina Faso in support of the Burkinabe jihadist group Ansarul Islam, though the group very rarely claims attacks. Despite Ag Alkassoum’s death during a French military operation in November 2018, the group remains active in conducting improvised explosive device (IED) and other attacks on Malian and UN forces. The area between Douentza, Boni, and Hombori remains one of the major areas of attacks recently against these forces, while also purportedly operating at times both with JNIM and groups close to JNIM like Ansarul Islam. The other represents a loose collection of fighters operating largely in the Sèrma forest near Burkina Faso, with the appellation “Katibat Sèrma” coined by the analyst Hèni Nsaibia.

ANSARUL ISLAM

This group began as a localised insurgency in the northern provinces of Burkina Faso, under the leadership of Malam Ibrahim Dicko. Dicko was a Peul commander linked to Ansar al-Din who was arrested by French forces in Mali in 2015 and then later released. The group’s first attack against Burkinabe forces was in December 2016, when they killed 12 gendarmes in Nassoumbou. The insurgency has quickly expanded since then. Today, Ansarul Islam is composed largely of Peul fighters and it conducts attacks across northern and eastern Burkina Faso, as well as operating on the other side of the Malian border. It is believed to be in close contact with members of Katibat Macina as well as Almansour Ag Alkassoum (before his death) and his fighters. It also operates increasingly along Burkina Faso’s border with Niger. When Malam Dicko died in 2017, he was replaced by his brother, Jafar Dicko, as leader.

THE ISLAMIC STATE IN THE GREATER SAHARA (ISGS)

This local branch of the Islamic State group (ISIS) was at first self-proclaimed, the outgrowth of a schism within MUJAO. The group’s leader, the former MUJAO commander Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraoui, declared his adherence to the Islamic State in May 2015, although ISIS only recognised the pledge of allegiance (bay’a) to its leader Abubakr al-Baghdadi in October 2016. ISGS began receiving regular attention from formal ISIS media outlets in spring 2019. The group operated first in western Niger and Ménaka, in north-eastern Mali, while also conducting several attacks in Burkina Faso near the border with Mali and an attack on a high-security prison near Niger’s capital Niamey in October 2016. ISGS fighters fought a battle in June 2015 with al-Mourabitoun fighters loyal to Mokhtar Belmokhtar, but subsequently the groups have avoided clashes. At times, ISGS has operated in proximity – and possibly even cooperation – with fighters from JNIM.

According to interviews with local observers as well as regional and international sources, ISGS has drawn many of its fighters from those native to the areas in which it operates, especially Nigerien Peul as well as Dawsahak fighters whose origins are in Ménaka and the Malian city of Gao. ISGS fighters were responsible for the deadly attack that killed four American soldiers and five Nigerien soldiers at Tongo Tongo in the province of Tillabéry, as well as dozens of attacks against Nigerien, Malian, and Burkinabe troops, militias like the Mouvement pour le Salut de l’Azawad (MSA), and Groupe d’Autodéfense Tuareg Imghad et Alliés (GATIA). It has in recent months expanded its territorial operations along the Niger-Burkina Faso border, as well as into the Gourma region south of Timbuktu in Mali.

Non-Jihadists

CMA

CMA is one of the signatory groups of the Algiers Peace Accords signed in June 2015. It is composed of the Mouvement National pour la Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA), the Haut Conseil pour l’Unité de l’Azawad (HCUA), and part of the Mouvement Arabe de l’Azawad (MAA-CMA). The CMA is ostensibly united around the formerly pro-independence movements in northern Mali, but it is really more an umbrella organisation that does not represent one unified ideology.

PLATEFORME

The Plateforme comprises several groups that favour Malian state authority, though it is also heavily implicated in local disputes and attempts at communal control. The Plateforme is the other signatory armed group of the 2015 Algiers Accords. The main groups that make up the Plateforme are: the Groupe d’Autodéfense Tuareg Imghad et Alliés (GATIA), the MAA-Plateforme, and the Coordination des mouvements et fronts patriotiques de résistance (CMFPR-1).

MOUVEMENT POUR LE SALUT DE L’AZAWAD (MSA)

The MSA formed in September 2016 under the leadership of Moussa Ag Acharatoumane, a young intellectual who was a founding member and political representative of the MNLA. However, as Gao- and Ménaka-based communities sought greater political representation and a larger role in local security with the planned implementation of the Algiers Accords, the MSA broke away from the CMA and especially from the MNLA. The MSA was at first a joint movement of largely Dawsahak as well as Chamanamass Tuareg communities, though the Chamanamass soon split away and constituted a separate MSA branch, referred to here as the MSA-C. The MSA-D is the component part of the alliance with GATIA (though not a part of the Plateforme), and continues to conduct security operations in the eastern part of the Gao region as well as in Ménaka. It has also often joined French forces in operations in the region. It has moved away from pushing for independence and now cooperates with the Malian government. These operations – described as counterterrorism operations largely against ISGS but also against JNIM – have prompted a series of attacks against its forces and assassinations of key MSA figures like the group’s former military commander Adam Ag Albachir in October 2017 and Hadama Ag Haynaha in April 2019. It has also conducted a number of local patrols meant to restore security and prevent theft of property and livestock, although it too has faced accusations of theft and abuses against civilians in the region.

COORDINATION DES MOUVEMENTS DE L’ENTENTE (CME)

The CME is a loose coalition of armed groups that are not formally part of the peace process in Mali, but advocate for their own inclusion in the process. These groups have largely localised power bases and split away either from the CMA (especially the MNLA) or the Plateforme. They include the MSA-C, the Coalition du Peuple pour l’Azawad based in Timbuktu and the Gourma, the Congrès Pour la Justice dans l’Azawad formed almost entirely of former MNLA members from the Kel Antessar Tuareg confederation based in and around Timbuktu, the Front Populaire de l’Azawad (FPA), and the Mouvement Populaire pour le Salut de l’Azawad, largely composed of Timbuktu-area Arab and some Tuareg populations, a portion of which recently announced that they had rejoined the MNLA. These groups participate in some parts of the peace process such as the Comité Technique de la Sécurité and the Mécanisme Opérationnel de Coordination (MOC), as well as the new accelerated DDR programme. But they are not participants in the Comité de Suivi des Accords meetings with the international community and cannot be full participants in the peace process without joining the CMA or the Plateforme.

DAN NA AMBASSAGOU

This group, whose name means “those who put their trust in God” in Dogon, operates in the central and eastern part of the Mopti region, in areas colloquially referred to as the “Pays Dogon”. In Mali, which is nearly 90 percent Muslim, the Dogon makes up a sizeable portion of the non-Muslim population, though there are also ethnic Dogon communities that are Muslim. Dan Na Ambassagou emerged in late 2016 from traditional hunters’ brotherhoods. They represent a loose coalition of largely Dogon self-defense militias that operate under the military authority of Youssouf Toloba. They are very present around Bankass, Bandiagara, Koro, and Mondoro, and are believed to have committed a series of massacres against Peul populations, including at Kolougon in January 2019 and Ogossagou in April 2019. They frequently attack Peul villages and encampments, alleging that jihadists affiliated with Katibat Macina take refuge there. They have also clashed with Peul self-defense groups, which they accuse of cooperating with jihadist fighters. Peul activists and NGO officials have also alleged that several former Malian military officers still in contact with the government are involved with Dan Na Ambassagou, and that their fighters have at times cooperated with Malian defense and security forces operating in their areas.

Other groups of local “hunters” sometimes referred to as Dozo – both Dogon communities and also Bambara speakers – exist in areas near Douentza, Djenné, and Segou. However, these groups are fluid and do not have the same kind of military organisation as a group like Dan Na Ambassagou, even as they have still been allegedly responsible for atrocities in these areas.

Foreign Actors

Operation Barkhane

The French-led Operation Barkhane succeeded Operation Serval in August 2014, but with a much wider geographic focus. The force, with approximately 4,500 soldiers, is spread out between Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad. While its headquarters is in N’Djamena, Chad’s capital, it also has fighter aircraft and bases for intelligence collection and operations in Niger’s capital Niamey, Agadez, Arlit, Tillabéry, and several other sites, as well as around 1,500 troops in northern Mali scattered between the large base at Gao, others at Kidal, Timbuktu, and Tessalit, and more recently a base at Gossi closer to central Mali as well as the border with Burkina Faso. France’s Special Operations Task Force for the region, Operation Sabre, is in Burkina Faso.

Operation Barkhane is France’s largest overseas operation, with a budget of nearly €600m per year. It engages in everything from combat patrols alongside Malian forces and partner militias to intelligence gathering and training to local development activities meant to fill the hole left by an absent government. Despite this range, French officials insist that Barkhane’s priority is counterterrorism and it has undertaken operations to kill important jihadist leaders, including two of the five founding leaders of the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa al-Muslimeen, JNIM) as well as Almansour Ag Alkassoum and a number of others.

THE EUROPEAN UNION

The European Union has two Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions in Mali and one in Niger. In Mali, these are the EU Training Mission (EUTM), which provides training for the Malian armed forces, and the EU Capacity and Assistance Programme (EUCAP) mission, which largely focuses on police and internal security forces. The EUCAP mission in Niger has since 2016 focused much more on migration, whereas the two missions in Mali remain focused on counterterrorism training, core military and police capacity building, and improving awareness of human rights. These missions do not deploy offensively or in the field in support of the forces they train, though they have faced attack at their base in Koulikoro as well as in Bamako. EUTM and EUCAP have expanded their operations to include trainings conducted in central and northern Mali, in part in response to concerns that they had overly focused their activities in southern Mali.

AFRICAN UNION (by DCAF)

– The political section aims to accompany the strenghtening of the benefits of peace and security; to promote the rule of Law and to contribute to the reinforcement of the democratic institutions in the Sahelian region, including the protection of Human Rights, capacity building for the national Human Rights institutions, the judicial sector and the organisations from the civil society. Through this project, the MISAHEL also works on humanitarian issues, especially in the Northern Region.

– The second section is dedicated to the security in the Sahelian Region. Its main objective is to oversee the efforts of the AU as regards the security challenges, and in particular conflicts, terrorism, and various organized crime networks.

– The last section focuses on the development and environmental issues in the region, such as the deterioration of the environment, and the consequences of underdevelopment.

These products are the results of academic research and intended for general information and awareness only. They include the best information publicly available at the time of publication. Routine efforts are made to update the materials; however, readers are encouraged to check the specific mission sites at https://minusma.unmissions.org/en or https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/minusma.

Index

Executive Summary / Current Political and Security Dynamics / Recent Situation Updates

Country Profile of Mali

Government/Politics / Geography / Military / Economy / Social / Information / Infrastructure

United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA)

Senior Leaders of Mission / Mandate / Strength / Deployment of Forces / Casualties / Mission’s Military and Police Activities / Security Council Reporting and mandate cycles / Background of Conflict / Actors of Conflict / Timeline