Congo (DRC) Country Profile – Social

Last update on: 3 June 2021

From https: Cia Website (Page last updated on June 03, 2021)

Population: 105,044,646 (July 2021 est.) / note: estimates for this country explicitly take into account the effects of excess mortality due to AIDS; this can result in lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality, higher death rates, lower population growth rates, and changes in the distribution of population by age and sex than would otherwise be expected

Nationality: Congolese

Ethnic groups: more than 200 African ethnic groups of which the majority are Bantu; the four largest tribes – Mongo, Luba, Kongo (all Bantu), and the Mangbetu-Azande (Hamitic) – make up about 45% of the population

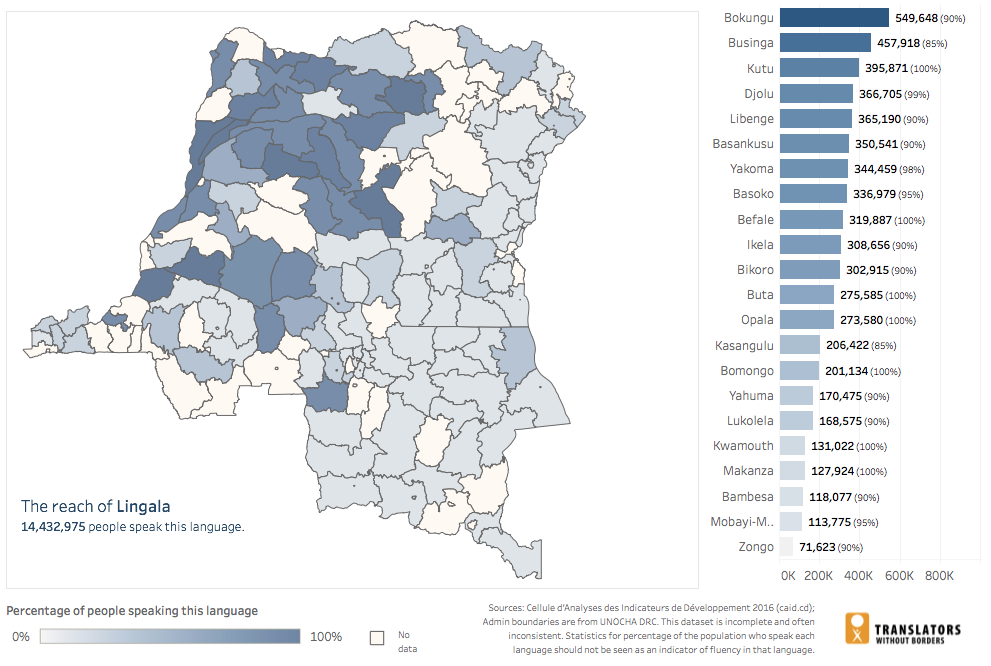

Languages: French (official), Lingala (a lingua franca trade language), Kingwana (a dialect of Kiswahili or Swahili), Kikongo, Tshiluba

Religions: Roman Catholic 29.9%, Protestant 26.7%, Kimbanguist 2.8%, other Christian 36.5%, Muslim 1.3%, other (includes syncretic sects and indigenous beliefs) 1.2%, none 1.3%, unspecified .2% (2014 est.)

Demographic profile:

Despite a wealth of fertile soil, hydroelectric power potential, and mineral resources, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) struggles with many socioeconomic problems, including high infant and maternal mortality rates, malnutrition, poor vaccination coverage, lack of access to improved water sources and sanitation, and frequent and early fertility. Ongoing conflict, mismanagement of resources, and a lack of investment have resulted in food insecurity; almost 30 percent of children under the age of 5 are malnourished. The overall coverage of basic public services – education, health, sanitation, and potable water – is very limited and piecemeal, with substantial regional and rural/urban disparities. Fertility remains high at almost 5 children per woman and is likely to remain high because of the low use of contraception and the cultural preference for larger families.

The DRC is a source and host country for refugees. Between 2012 and 2014, more than 119,000 Congolese refugees returned from the Republic of Congo to the relative stability of northwest DRC, but more than 540,000 Congolese refugees remained abroad as of year-end 2015. In addition, an estimated 3.9 million Congolese were internally displaced as of October 2017, the vast majority fleeing violence between rebel group and Congolese armed forces. Thousands of refugees have come to the DRC from neighboring countries, including Rwanda, the Central African Republic, and Burundi.

Other information about Congo (DRC) – Social:

a. Rule of Law. The police have violently cracked down on internal dissent. Protests and demonstrations will continue as the political election process—and progress—remains in doubt. Most legal justice is implemented by external agencies, such as the International Criminal Court (ICC) rulings against a former Congolese rebel leader (and vice president) guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity (for the rapes and killings committed by his troops in the Central African Republic from 2003 to 2006). It was the first such case to focus on the use of sexual violence as a tool of war.

b. Human Rights. The DRC human rights record remains problematic, with unlawful killings, disappearances, torture, and rape committed by all armed groups, and arbitrary arrest and detention carried out by state security forces. All actors continued to recruit and retain child soldiers and to compel forced labor by adults and children. There appears to be negligible legal accountability for these activities. As an example, no investigation was completed in regards to mass grave found in 2015 However, the 2017 arrest of seven DRC military officers, charged with war crimes based on video evidence, is a noteworthy exception. The rationale for—and perpetrators of—the continued communal violence is unclear:

“While government officials have insisted that the recent Ituri violence is the consequence of inter-ethnic tensions between the ethnic Lendu and Hema communities, local leaders and survivors we spoke to have been left baffled. While low-level tensions existed – like in many parts of Congo – the communities were not preparing to go to war with each other. Many survivors referred to a “hidden hand” when describing those who might be behind the attacks: Seemingly professional killers came into their villages and hacked people to death with notable efficiency and brutality, in what appeared to be pre-meditated and well-planned attacks. Some alleged that government officials may be involved.”

In addition, in April 2018 the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported: “at least 27 cases in recent months of security forces briefly detaining, threatening, or assaulting journalists as they covered violence and protests calling for President Joseph Kabila to step down.”

c. Humanitarian Assistance. In March 2018, the UN Security Council met to discuss the humanitarian situationin the DRC, calling it “catastrophic”:

“…at least 13.1 million Congolese in need of humanitarian assistance, including more than 7.7 million severely food insecure people…the very high number of internally displaced persons in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which has more than doubled in the last year to more than 4.49 million, and the 540,000 refugees in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as well as the more than 714,000 refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo in neighboring [sic] countries as a result of ongoing hostilities.”

They further “expressed concern at increased impediments to humanitarian access in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo resulting from insecurity and violence, as well as continued attacks against humanitarian personnel and facilities.”

Almost 30 percent of children under the age of 5 are malnourished despite fertile soil and other vast power and mineral resources. Just over half of the total population has access to improved water, with better access in urban areas compared to rural areas. In contrast, almost 75% of the population has no access to improved sanitation, with negligible difference between urban and rural areas. Consequently, the risk of disease is very high. In 2016, 25,030 people died from cholera, malaria, measles, or yellow fever. Malaria was the leading cause of death and hospitalization, with over 14.1 million cases reported from

| In February 2017, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), announced a three-year Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP), requesting “$748 million to address the most critical needs of 6.7 million people…to allow humanitarian partners to focus on preparedness and flexible, long-term funding…between now and 2019.” Reductions in U.S. Government funding for aid significantly impact the programs in the DRC. |

January to December 2016, including over 23,800 deaths. The outbreak of “Angola Yellow Fever” started in December 2015, was declared “the end” in February 2017, after almost 3,000 suspected cases reported.

d. Protection of Civilians (PoC)

The Protection of Civilians (PoC) has always been a challenge for MONUSCO, given the size of the territory it has to protect and significant insecurity due to the activity of armed groups in the eastern territories. Over time, MONUSCO has established different mechanisms for responding to threats against civilians, many of which are outlined in the text box below. These approaches have also served as a model for other peacekeeping missions. The Joint Protection Teams (JPTs) were meant to bring the civilian and military components of the mission into closer alignment, while the Must-Should-Could Matrix allowed all aspects of the mission to set realistic expectations about protection priorities. In order to foster better communication with vulnerable populations, the civilian component of the mission established an elaborate network of community liaisons. These liaisons helped establish an alert network that serves as an early warning tool for threats against the population. Over time, MONUSCO sought to have better visibility on the armed groups that posed a threat to the population, which led to the procurement of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for the mission in 2015.

| Protection Tools Established by MONUSCO Joint Protection Teams (JPTs): Established after the 2008 Kiwanja (North Kivu) massacre of more than 100 people near a MONUC camp. JPTs are multi-disciplinary teams deployed to hotspots needing protection to analyze protection needs and define preventive and responsive interventions to address them. JPTs bring together the military, police, and civilian components of the Mission for a multidimensional analysis of threats and protection needs, and to devise preventive and responsive protection plans in given field locations. Must-Should-Could Matrix: A joint planning exercise between MONUSCO and the humanitarian community to help identify priority areas according to the level of threat and degree of vulnerability of the local population in given hotspots. Community Liaison Assistants (CLAs): National staff working alongside troops in military bases to enhance interaction between the Force and local communities and authorities, analyze protection needs, and inform protection strategies and plans. Community Alert Networks (CANs): Early-warning mechanism based on a network of focal points in communities surrounding MONUSCO bases. CANs stay in touch via radio or mobile phones to alert one another in case of an imminent threat. Lately, they have developed a specific phone number (like 911). Local Security Committees (LSCs): Established at the provincial and territorial level to provide a framework through which they can engage with local officials and civil society. Prosecution Support Cells: Established to bolster military prosecution capabilities. Source: Various Tools for the Protection of Civilians, Norwegian Institute of International Affairs |

- Children and Armed Conflict (CAAC)

Among the above protection concerns, considerable progress has been made with reducing the use of child soldiers by the FARDC (Norwegian Institute). From 2014-2017, a total of 7,736 children (7,125 boys, 611 girls) were separated from armed groups and demobilized by MONUSCO and other UN agencies (UNSC Report on Children and Armed Conflict in the DRC 2018).[i] However, numerous armed groups continued to forcibly recruit children and use them as fighters, human shields, tax and food collectors, porters, cooks, mine laborers, and sexual slaves or “wives” to armed forces (Ibid, UNSC 2018).

e. Women, Peace, and Security (WPS)

Women, Peace, and Security considerations are based on SCRES 1325, which is comprised of four pillars; participation of women in the political process and security sector, protection of women and girls from violence, prevention of gender-based violence, and ensuring that relief and recovery activities account for different needs within the population by age and gender, such as the special needs of women and girls, and boys and men.

The United Nations has encouraged nations to develop their own National Action Plans (NAPs) on implementing SCRES 1325. The DRC Ministry for Gender, Children, and Family developed a NAP in 2010, which was updated in September 2018. The NAP highlights that equality between men and women and the elimination of sexual violence is within Articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution.

| Since the first NAP in 2010, President Kabila nominated the first female generals in the Armed Forces of (FARDC) and nominated other senior officers for promotion. The police force has 10% of female officers. Ongoing difficulties in the security sector are due to the low overall rate of female participation in the force, which makes it harder to promote women to command positions, and women also need to be recruited to join the armed forces. DRC NAP 2018 |

The plan further acknowledges ongoing challenges to achieving progress on WPS; insufficient female participation in governance, low number of women in command positions in the security sector, the persistence of violence, impunity for human rights violations, and insufficient funding to implement the first plan have led to gaps in progress.

The 2018 plan sets a target for 20% female participation in peace processes and political negotiations at all levels of government. The NAP also calls for an increase in women’s participation in the security sector, above current levels; Army (2.8%), Police (6.7%), and Judicial Sector (19.4%). The demobilization of women who have been forcibly recruited into non-state armed groups is also a priority objective. For examples of women in the armed forces, see We are fighters too (Washington Post 07 March 2019).

The NAP also calls for the demobilization of armed groups and a reduction in small arms that proliferate violence, an increase in police and justice sector action to hold perpetrators accountable for sexual violence, and the promotion of women’s economic opportunities as a mechanism for reducing inequalities exacerbated by conflict.

- Participation: although the Constitution of the Democratic Republic of the Congo lays a foundation for gender equality, women fill less than 10% of key government offices. However, in 2019, Janine Mabunda was selected to head the Congolese National Assembly. She was nominated by former President Kabila, further signifying his considerable influence over the new government (Africa News 26 April 2019).

- Protection

- Conflict-Related Sexual Violence (CRSV): despite protection actions taken by the mission, conflict-related sexual violence remains a major concern in the DRC. In 2018, MONUSCO documented 1,049 cases of CRSV against 605 women, 436 girls, 4 men, and 4 boys. Of these cases, 741 were attributed to armed groups and 308 were attributed to the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Congolese National Police. The majority of verified incidents occurred in North and South Kivu Provinces (UN Office Special Representative for Sexual Violence in Conflict 2019).[ii]The UN Special Representative for Sexual Violence in Conflict has urged the Government of the DRC to increase state and security presence in mining areas and to vet and train armed forces. Ensuring accountability for offenses by upholding a zero-tolerance policy and bringing offenders to justice is also key to ending the cycle of sexual violence. While the Security Council has sought to strengthen monitoring and reporting mechanisms for CRSV, most notably from the recent passage of UNSCRES 2467 on 29 April 2019 calling for stronger reporting mechanisms, some member states have resisted this approach.

- Prevention: in 2014, the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) developed an action plan on the prevention of sexual violence by the military. Every commander working in the FARDC signed the declaration (UN Women). The pledge outlines the following commitments:

- Respecting human rights and international humanitarian law in relation to sexual violence; Taking action against sexual violence committed by soldiers under their command;

- Ensuring the prosecution of alleged perpetrators of sexual violence under their command;

- Facilitating access to areas under their command to military prosecutors and handing over perpetrators within their command that are under investigation, have been indicted or convicted;

- Undertaking disciplinary measures against soldiers suspected of involvement in sexual violence

- Reporting to the FARDC leadership any incidents or allegations committed within their AoR

- Sensitizing soldiers under their command about the zero-tolerance policy on sexual violence

- Taking specific measures to ensure the protection of victims, witnesses, judicial actors and other stakeholders involved in addressing sexual violence.

The extent to which this pledge has reduced instances of sexual violence by the FARDC is unclear. However, UN reports indicate that a high percentage of conflict-related sexual violence in the DRC is committed by non-state actors.

- Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA): according to the UN’s database, there have been 6 reports of sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) against MONUSCO personnel (civilians and uniformed) in 2019, and 19 reports in 2018. These allegations include rape, transactional sex, and exploitative relationships involving troops from South Africa, Morocco, Romania, and Nigeria.[iii]

| South African personnel SEA allegations are significantly more than those ascribed to any other MONUSCO T/PCC contingent. Therefore, at the invitation of South Africa, MONUSCO’s Conduct and Discipline Team directed pre-deployment “Prevention of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse” training for 820 South African peacekeepers in May 2017. |

f. Relief and Recovery

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) facilitates a cluster system of humanitarian response, including a Protection Cluster which conducts assessments and coordinates action on human rights, displacement, and the protection of civilians. The Protection Cluster is co-lead by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The Gender-Based Violence (GBV) Area of Responsibility (AoR) is a subcomponent of the protection cluster, led by the United Nations Agency for Children (UNICEF) with the participation of UN Women.

According to UNHCR, there are nearly 4.5 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) inside the DRC, and 750,000 refugees from the DRC outside the country. Additionally, Congo hosts 535,805 refugees from Rwanda, Central African Republic and South Sudan (UNHCR Fact Sheet DRC April 2020).

[i] UNSC Report on Children and Armed Conflict in the DRC, S/208/502, 25 May 2018 https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2018/502&Lang=E&Area=UNDOC

[ii]UN Office of the Special Representative for Sexual Violence in Conflict, Report on the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), 2019 https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/countries/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/

[iii] UN Office of Conduct and Discipline, 2019 https://conduct.unmissions.org/sea-overview

Other Social sources:

https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/democratic-republic-congo

These products are the results of academic research and intended for general information and awareness only. They include the best information publicly available at the time of publication. Routine efforts are made to update the materials; however, readers are encouraged to check the specific mission sites at https://monusco.unmissions.org/en or https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/monusco.

Index

Executive Summary / Current Political and Security Dynamics / Recent Situation Updates

Congo Country Profile

Government/Politics /Geography / Military / Economy / Social / Information / Infrastructure

United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO)

Senior Leaders of the Mission / Mandate / Strength / Deployment of Forces / Casualties / Mission´s Political Activities / Security Council Reporting and Mandate Cycles / Background of Conflict / Timeline