Mali Country Profile – Military

From Cia Factbook (Page last updated on October 09, 2020)

Military and security forces:

Malian Armed Forces (FAMa): Army (Armee de Terre), Republic of Mali Air Force (Force Aerienne de la Republique du Mali, FARM); National Gendarmerie; National Guard (Garde National du Mali) (2019) / note(s): the Gendarmerie and the National Guard are under the authority of the Ministry of Defense and Veterans Affairs (Ministere De La Defense Et Des Anciens Combattants, MDAC), but operational control is shared between the MDAC and the Ministry of Internal Security and Civil Protection.

The Gendarmerie’s primary mission is internal security and public order; its duties also include territorial defense, humanitarian operations, intelligence gathering, and protecting private property, mainly in rural areas.

The National Guard is a military force responsible for providing security to government facilities and institutions, prison service, public order, humanitarian operations, some border security, and intelligence gathering; it has special units on camels (the Camel Corps) for patrolling the deserts and borders of northern Mali.

Military expenditures:

- 2.7% of GDP (2019)

- 2.9% of GDP (2018)

- 3% of GDP (2017)

- 2.6% of GDP (2016)

- 2.4% of GDP (2015)

Military and security service personnel strengths: estimates for the size of the Malian Armed Forces (FAMa) vary; approximately 19,000 total troops (13,000 Army; 800 Air Force; 3,000 Gendarmerie; 2,000 National Guard)(2019 est.).

Military equipment inventories and acquisitions: the FAMa’s inventory consists primarily of Soviet-era equipment, although in recent years it has received limited quantities of mostly second-hand armaments from a variety of countries; since 2010, the leading suppliers have been Brazil, Bulgaria, France, Russia, South Africa, Spain, and the United Arab Emirates (2019 est.).

Military service age and obligation: 18 years of age for selective compulsory and voluntary military service (men and women); 2-year conscript service obligation (2014)

Military – note: prior to the August 2020 coup, the Malian military had intervened in the political arena at least five times since the country gained independence in 1960; two attempts failed (1976 and 1978), while three succeeded (1968, 1991, and 2012); the military collapsed in 2012 during the fighting against Tuareg rebels and Islamic militants.

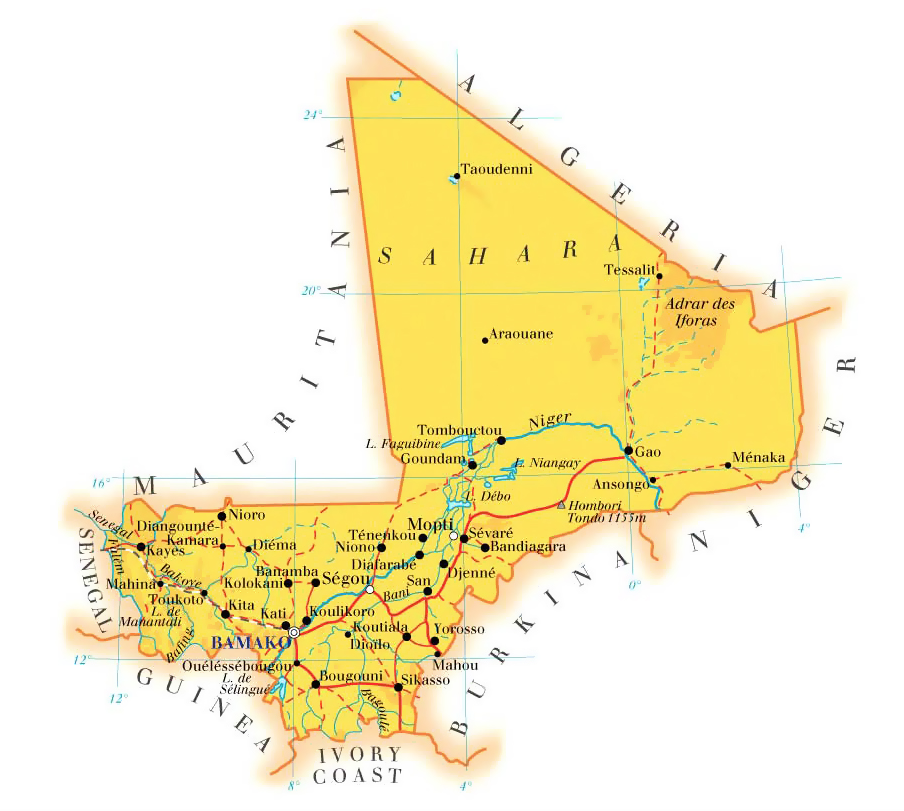

Since 2017, the FAMa, along with other government security and paramilitary forces, has conducted multiple major operations against militants in the eastern, central, and northern parts of the country; up to 4,000 troops reportedly have been deployed; the stated objectives for the most recent operation (Operation Maliko in early 2020) was to end terrorist activity and restore government authority in seven of the country’s 10 regions, including Mopti, Ségou, Gao, Kidal, Ménaka, Taoudénit, and Timbuktu.

Mali is part of a five-nation anti-jihadist task force known as the G5 Sahel Group, set up in 2014 with Burkina Faso, Chad, Mauritania, and Niger; it has committed 1,100 troops and 200 gendarmes to the force; in early 2020, G5 Sahel military chiefs of staff agreed to allow defense forces from each of the states to pursue terrorist fighters up to 100 km into neighboring countries; the G5 force is backed by the UN, US, and France; G5 troops periodically conduct joint operations with French forces deployed to the Sahel under Operation Barkhane.

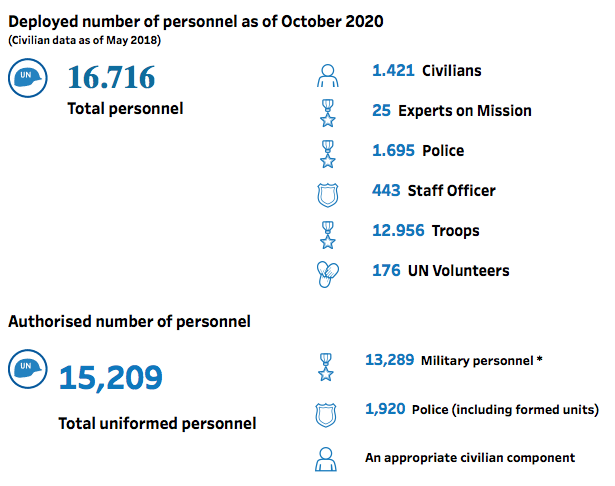

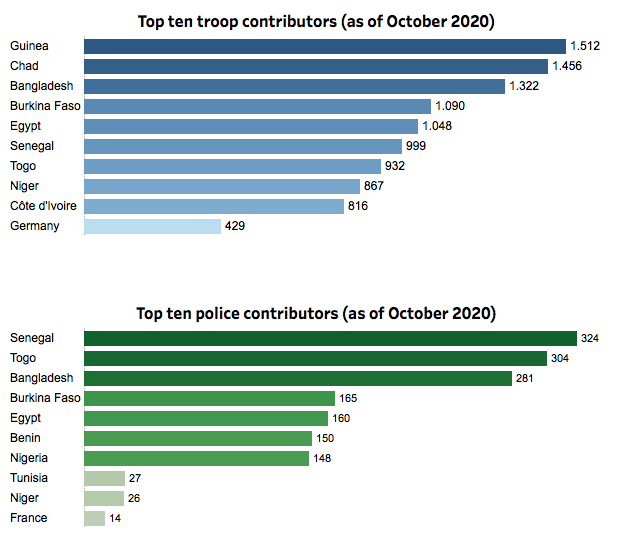

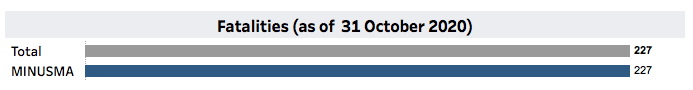

The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) has operated in the country since 2013; the Mission’s responsibilities include providing security, rebuilding Malian security forces, supporting national political dialogue, and assisting in the reestablishment of Malian government authority; as of March 2020, MINUSMA had around 15,500 military, police, and civilian personnel deployed.

The European Union Training Mission in Mali (EUTM-M) also has operated in the country since 2013; the EUTM-M provides advice and training to the Malian Armed Forces and military assistance to the G5 Sahel Joint Force; as of August 2020, the mission included more than 600 personnel from 28 European countries (2020).

Other information on Mali – Military / Security:

from Mali SSR Background Note, DCAF

a. Defence

The Malian Armed Forces consist of the National Defence, composed of the Air Force, the Army and the National Guard, alongside the National Gendarmerie, all of whom fall under the authority of the Ministry of Armed Forces and Former Combatants (MoAF).

The President is the supreme commander of the armed forces, and the Prime Minister is responsible for the implementation of the national defence policy. The Armed Forces fall under the MoAF, and consist of 13,800 personnel. The armed forces are also used during peacetime as an auxiliary force to maintain public order. As of 2014, 7% of the army and 6% of the air force were composed of women.

There has always been tension between the civilian population and military forces because of Mali’s history of authoritarian rule. This relationship has been further damaged by the recent coup and continued influence of the ex-Junta leaders on the interim government. Furthermore, Mali’s military remains deeply divided, underpaid and unable to effectively defend the country from insurgent groups. Security forces have also been accused of violating basic human rights and attacking individuals who belong to specific ethnic groups thought to be in collusion with the insurgents.

b. Police and Internal Security

Internal security and public order are ensured by the National Police, the National Gendarmerie, and the National Guard, which report to the Ministry of Security and Civil Protection (MSPC) for employment. The two last institutions remain attached to the Ministry of Defence and Veterans (MDAC) for their administrative and budgetary management. The 2015 Peace Agreement also allows for the creation of territorial police forces in the regions.

- The National Police falls under the authority of the Ministry of Internal Security and Civil Protection (MoI). It is estimated to employ over 6,000 individuals, 700 of whom are women. The National Police’s mandate focuses primarily on the protection of people and property, identification and record of criminal offenses, gathering evidence, finding and arresting perpetrators, and gathering intelligence to inform government decision-making.

- The Judicial Police, an integral part of the National Police, is tasked specifically with reporting violations of criminal law, gathering evidence, tracking down suspects and supporting investigating authorities once a case is opened.

- The National Gendarmerie shares a number of security-related responsibilities with the National Police and the National Guard, including maintaining public order, collecting intelligence, and protecting private property. Having military status, it is also entrusted with territorial defense. As of 2015, it is estimated that the gendarmerie counts 4,000 individuals, 100 of whom are women.

- The National Guard is responsible for providing security to political and administrative institutions as well as contributing to the maintenance of public order and the territorial defense of Mali. The National Guard falls under the MoAF for administrative affairs and the MoI for deployment. As of 2015, it is estimated that the National Guard contains 3,000 individuals, 100 of whom are women.

These products are the results of academic research and intended for general information and awareness only. They include the best information publicly available at the time of publication. Routine efforts are made to update the materials; however, readers are encouraged to check the specific mission sites at https://minusma.unmissions.org/en or https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/minusma.

Index

Executive Summary / Current Political and Security Dynamics / Recent Situation Updates

Country Profile of Mali

Government/Politics / Geography / Military / Economy / Social / Information / Infrastructure

United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA)

Senior Leaders of Mission / Mandate / Strength / Deployment of Forces / Casualties / Mission’s Military and Police Activities / Security Council Reporting and mandate cycles / Background of Conflict / Actors of Conflict / Timeline