MINUSMA – Timeline Since 2007 – Conflict in Mali

from BBC Mali Profile – Timeline

2007 August – Suspected Tuareg rebels abduct government soldiers in separate incidents near the Niger and Algerian borders.

2008 May – Tuareg rebels kill 17 soldiers in attack on an army post in the northeast, despite a ceasefire agreed a month earlier.

2008 December – At least 20 people are killed and several taken hostage in an attack by Tuareg rebels on a military base in northern Mali.

2009 February – Government says the army has taken control of all the bases of the most active Tuareg rebel group. A week later, 700 rebels surrender their weapons in ceremony marking their return to the peace process.

2009 May – Algeria begins sending military equipment to Mali in preparation for a joint operation against Islamic militants linked to al-Qaeda.

2009 August – New law boosts women’s rights, prompts some protests.

2010 January – Annual music event – Festival in the Desert – is moved from a desert oasis to Timbuktu because of security fears.

2010 April – Mali, Algeria, Mauritania and Niger set up joint command to tackle threat of terrorism.

2012 January – Fears of new Tuareg rebellion following attacks on northern towns which prompt civilians to flee into Mauritania.

2012 March – Military officers depose President Toure ahead of the April presidential elections, accusing him of failing to deal effectively with the Tuareg rebellion. African Union suspends Mali.

2012 April – Tuareg rebels seize control of northern Mali, declare independence.

Military hands over to a civilian interim government, led by President Dioncounda Traore.

2012 May – Junta reasserts control after an alleged coup attempt by supporters of ousted President Toure in Bamako.

Pro-junta protesters storm presidential compound and beat Mr Traore unconscious.

The Tuareg MNLA and Islamist Ansar Dine rebel groups merge and declare northern Mali to be an Islamic state. Ansar Dine begins to impose Islamic law in Timbuktu. Al-Qaeda in North Africa endorses the deal.

2012 June-July – Ansar Dine and its Al-Qaeda ally turn on the MNLA and capture the main northern cities of Timbuktu, Kidal and Gao. They begin to destroy many Muslim shrines that offend their puritan views.

2012 August – Prime Minister Cheick Modibo Diarra forms a new government of national unity in order to satisfy regional demands for a transition from military-dominated rule. The cabinet of 31 ministers includes five seen as close to coup leader Capt Amadou Sanogo.

2012 Autumn-Winter – Northern Islamist rebels consolidate their hold on the north. They seize strategically important town of Douentza in September, crossing into the central part of Mali and closer to the government-held south-west.

2012 November – The West African regional grouping Ecowas agrees a coordinated military expedition to recapture the north, with UN and African Union backing. Preparations are expected to take several months.

2012 December – Prime Minister Cheick Modibo Diarra resigns, allegedly under pressure from army leaders who oppose plans for Ecowas military intervention. President Traore appoints a presidential official, Django Sissoko, to succeed him. The UN and US threaten sanctions.

2013 January – Islamist fighters capture the central town of Konna and plan to march on the capital. President Traore asks France for help. French troops rapidly capture Gao and Timbuktu and at the end of the month enter Kidal, the last major rebel-held town. European countries pledge to help retrain the Malian army.

2013 April – France begins withdrawal of troops. A regional African force helps the Malian army provide security.

2013 May – An international conference pledges $4bn to help rebuild Mali.

2013 June – Government signs peace deal with Tuareg nationalist rebels to pave way for elections. Rebels agree to hand over northern town of Kidal that they captured after French troops forced out Islamists in January.

2013 July-August – Ibrahim Boubacar Keita wins presidential elections, defeating Moussa Mara.

France formally hands over responsibility for security in the north to the Minusma UN force.

2013 September – President Keita appoint banking specialist Oumar Tatam Ly prime minister.

2013 September-November – Government relations with Tuareg separatists in the north steadily worsen, with occasional clashes.

2013 December – Parliamentary elections give President Keita’s RPM 115 out of 147 seats.

France announces 60% reduction in troops deployed in Mali to 1,000 by March 2014.

2014 April – President Keita appoints former rival Moussa Mara prime minister in a bid to curb instability in the north.

2014 May – Fragile truce with Tuareg MNLA separatists breaks down in north. Separatists seize control of Kidal city and the town of Menaka, Agelhok, Anefis and Tessalit.

2014 September – Government, separatists begin new round of talks in Algeria to try end conflict over northern Mali, or Azawad as the secessionists call it.

Separatist MNLA opens an ”Azawad embassy” in the Netherlands.

2014 October – Nine UN peacekeepers killed in the north-east – the deadliest attack so far on its mission in Mali.

2015 January – Mali’s health minister says the country is free of the Ebola virus, after 42 days without a new case of the disease since October.

2015 April – Upsurge in fighting as Coordination of Azawad Movements northern rebels clash with UN peacekeepers in Timbuktu and seize town of Lere, try to recapture Menaka from pro-government militia.

2015 May – French troops kill leading al-Qaeda commanders Amada Ag Hama and Ibrahim Ag Inawalen in northern raid. Both were suspected of kidnapping and killing French citizens.

A peace accord to end the conflict in the north of Mali is signed by the government and several militia and rebel factions.

2015 June – Government and ethnic Tuareg rebels sign peace deal aimed at ending decades of conflict. The government gives the Tuareg more regional autonomy and drops arrest warrants for their leaders.

2015 July – Craftsmen in Mali working for the United Nations rebuild the world-renowned mausoleums in Timbuktu which were destroyed by Islamists in 2012.

2015 August – Seventeen people killed in attack by suspected Islamist militants on a hotel in the central Malian town of Sevare

2015 November – Islamist gunmen attack the luxury Radisson Blu hotel in the capital Bamako, killing 22.

2016 August – Several attacks on foreign forces. More than 100 peacekeepers have died since the UN mission’s deployment in Mali in 2013, making it one of the deadliest places to serve for the UN.

A Malian jihadist is found guilty of ransacking the fabled desert city of Timbuktu. He expressed regret in the unprecedented trial before the International Criminal Court.

2017 January – At least 37 people are killed by a car bomb at a military camp in Gao housing government troops and former rebels brought together as part of a peace agreement.

2017 February – Malian soldiers and rival militia groups including Tuareg separatists take part in a joint patrol, a key part of a peace agreement reached in 2015.

2017 April – President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita announces a new government, appointing close ally Abdoulaye Idrissa Maiga as prime minister.

2017 June – Al-Qaeda-aligned group Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimeen claims responsibility for an attack on an hotel popular with Westerners east of Bamako, killing two civilians.

2018 January – Some 14 soldiers are killed in a suspected Islamist attack on a military base at Soumpi. Elsewhere, 26 civilians die after their vehicle hits a landmine.

2018 June – Mali prepares for a presidential election amid Islamist violence and demonstrations pressing for the vote to be free and fair.

These products are the results of academic research and intended for general information and awareness only. They include the best information publicly available at the time of publication. Routine efforts are made to update the materials; however, readers are encouraged to check the specific mission sites at https://minusma.unmissions.org/en or https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/minusma.

Index

Executive Summary / Current Political and Security Dynamics / Recent Situation Updates

Country Profile of Mali

Government/Politics / Geography / Military / Economy / Social / Information / Infrastructure

United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA)

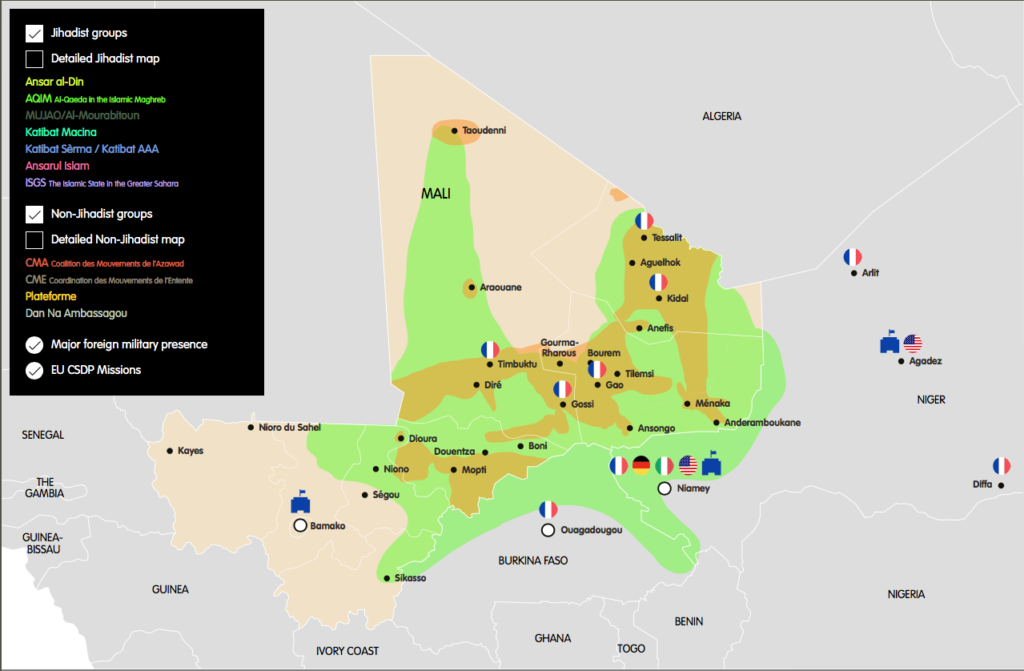

Senior Leaders of Mission / Mandate / Strength / Deployment of Forces / Casualties / Mission’s Military and Police Activities / Security Council Reporting and mandate cycles / Background of Conflict / Actors of Conflict / Timeline